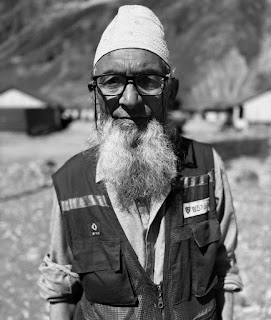

Haji Abdul Lone

Reflecting on his youth, Haji Abdul recalls how life in Matayen was challenging, with basic necessities like rice, salt, and cooking oil being sourced from Srinagar. At that time, corn was the staple food, while rice was considered a luxury. Due to limited road access, villagers had to transport supplies on foot or horseback across the Zojila Pass, a journey that took 5-6 days for each round trip. Poverty was widespread, and many villagers worked as laborers to make ends meet. Abdul’s father, Munnawar Lone, would make trips to Leh as a porter, carrying goods like tea, salt, and kerosene for a contractor.

Today, the only crop cultivated in the village is barley, which also depends on the erratic weather in Matayen. Livestock, which once included goats and sheep, has also declined in numbers over the past two decades, with most families now keeping only one cow for milk. Despite these changes, some aspects of the village’s heritage remain, such as the remnants of the shagarak (polo ground), a reminder of the once-popular sport. Traditional dance and music were once integral parts of wedding celebrations in Matayen, though these customs have largely faded over time.

Haji Abdul recalls a significant moment in Matayen’s history when Farooq Abdullah, the former Chief Minister of Jammu and Kashmir, visited the village. During his visit, Abdullah suggested relocating Matayen from Ladakh to Kashmir, citing its remoteness and the fact that most of its residents speak Kashmiri. Revenue officials were dispatched to survey the area, and the proposal seemed poised for consideration. However, the plan was eventually abandoned.

Looking back, Haji Abdul and the other residents of Matayen are thankful that the move never went through. They are relieved that their village remained part of Ladakh, preserving its unique identity, and are optimistic about the future, particularly with the upcoming Zojila tunnel. Once completed, the tunnel is expected to transform life in the region by providing year-round connectivity, improving access to essential goods, and opening up new opportunities for trade and tourism.

Haji Abdul shared an intriguing phenomenon in Matayen related to a lesser-known mountain peak called Kutthar, in the local dialect. The villagers believe that the mountains are home to fairies, and in his youth, Haji Abdul often observed two pigeons descending from the peak—a sight that has since stopped. Occasionally, he would also see mysterious lights moving along the nala (stream) that flows from the mountains behind the village. Once, he even heard a soothing melody emanating from the mountains. Stepping outside to investigate, he could hear the music clearly but saw no source for the sound.

Haji Gulam Mohd, at the site where once a building associated with Maharaja Hari Singh stood

Haji Gulam Mohd, 74, from Matayen, spent his life working in road construction, supplementing his modest income with small trading activities. Reflecting on his youth, he recalls how the people of Matayen would carry essential supplies like salt and other goods from Kashmir on foot, transporting them on their backs. In the mid-1980s, around the month of April, Haji Gulam himself made the journey, bringing 50 kg of onions across the Zojila on his back. He bought the onions for Rs. 4 per kg and sold them in Matayen for Rs. 6 per kg. He also bought apricots in Kargil for Rs. 15 per kg and sold them in Matayen for Rs. 20 per kg.

Although few historical structures remain in Matayen, Haji Gulam mentioned two sites connected to Maharaja Hari Singh of Kashmir. One was an old road built by the Maharaja, running through the village and linking to the Matayen-Pandaras route. The other, now barren, once housed a building where the Maharaja reportedly rested—likely the Matayen guesthouse, noted in early 20th-century travelogues as a stopover after crossing Zojila. When asked about Matayen’s mysterious Kutthar Peak, Haji Gulam shared an interesting story: He himself had once attempted the climb but had to turn back due to heavy rain. He then mentioned that years ago, a man named Nazeer from Pandaras village had successfully climbed Kutthar and still lives in Pandaras.

Abdul Wahab with Attaullah Lone. The Kutthar is the peak straight up between the two men

Abdul Wahab, from Pandaras village in Kargil and the brother of Nazeer—the only person to have ever climbed Kutthar—shares a deep belief in the mystical aura surrounding the peak. He, along with Attaullah Lone, a member of the aristocratic Dombapas family of Pandaras, took the author to a vantage point on the Leh-Srinagar highway. From there, one can see a distinct tower-like formation atop a mountain near Matayen, which the locals identify as the revered peak of Kutthar. Much like Haji Abdul from Matayen, Abdul Wahab has had his own experiences that suggest something otherworldly about Kutthar. He too claims to have heard music emanating from the mountains for which he has no explanation.

Nazeer Ahmed

On their descent, Nazeer and friend discovered a more accessible route. Once back down, they stopped by a nearby Bakarwal camp to rest and enjoy a cup of chai, sharing the story of their successful climb. Word of their accomplishment spread quickly throughout the region, and their journey became a celebrated achievement in the quiet local community.