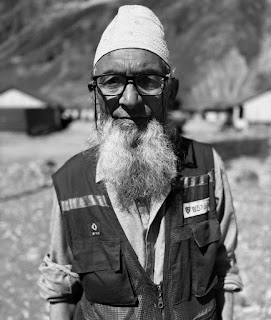

Situated 23 kilometres from Kargil on the way to Dras, Kaksar is one of the region's most beautiful yet unexplored gems. The village is home to Shina-speaking Dards, an indigenous ethnic group native to northern India. The name "Kak-Sar" is believed to be derived from the word "Sar" in the local Shina language, meaning a water body or river, symbolizing a place surrounded by water bodies. According to Haji Najaf Ali, a 73-year-old retired police officer and one of the most well-versed individuals regarding the history and culture of Kaksar, the village was originally known as Sukui, named after Suko, an ancestor believed to have been the first settler in the area.

As a young boy, Haji Najaf lived in Kargil while attending the Kargil Middle School, where the renowned Ladakhi educationist Eliezer Joldan served as headmaster. Joldan's remarkable contributions to advancing education in Ladakh during the early years after India’s independence earned him lasting recognition, with the present-day Leh College named in his honor. While still a teenager, Haji Najaf embarked on his journey into public service with the guidance of Akbar Ladakhi, a prominent figure from Leh and the then-SDM of Kargil, who helped him secure a position in the Home Guards. Shortly afterward, the 1965 Indo-Pakistan War erupted, and young Najaf was entrusted with the vital responsibility of guarding the bridge connecting Kaksar to the main highway. Vigilantly monitoring movements across the bridge, he also provided essential support to the army by arranging horses and manpower.

Following the war, Najaf was stationed at a government storehouse in Kargil. While serving there, his meticulous record-keeping skills caught the attention of Konchok Chospel, the Superintendent of Police (SP) of undivided Ladakh, which then included both Leh and Kargil. SP Chospel, impressed by Najaf’s abilities, encouraged him and two others from the region to join the police department. This marked the beginning of Haji Najaf’s long career in law enforcement.

Despite spending much of his life away from Kaksar due to postings in Leh and Kashmir, Najaf fondly reflects on his early days in the village. He remembers the visits of traders, locally known as Nyirings, from Wakah and Mulbek villages, who brought salt to Kaksar. Following local customs, these traders carried their own tea cups to avoid sharing utensils. As money was rarely used at the time, Najaf believes the Nyirings likely bartered salt for wool, as villagers maintained large herds of sheep and goats. The villagers sourced Pul (Ladakhi soda) and Chapak (tea bricks) from the Kargil bazaar. The Pul came from Nubra, while the tea, known locally as Kargili Chai, was brought from Leh. However, this tea was considered inferior to the more favored Punjabi Chai, supplied by a well-known army contractor Sardar Khem Singh, a Punjabi whose family had settled in Kargil.

Najaf shares a captivating story about Khem Singh, in the 1960s. During a visit to the Kargil treasury to withdraw money, Khem Singh inadvertently left a bag containing Rs. 60,000 hanging on a tree near the building. Unaware of his mistake, he carried on with his journey, traveling to Leh and eventually boarding an army plane to Chandigarh. Upon realizing his oversight, Khem Singh returned to Kargil with little hope of recovering the money. To his amazement, the bag was still there, untouched, hanging on the same tree where he had left it. A meeting was convened at the Islamia School to investigate the matter. After verifying the details of Khem Singh’s claim, the elders in Kargil returned the bag to him.

Najaf also recalls the prominent leaders of his time, including Munshi Habibullah of the National Conference, Ibrahim Shah Agha of the Congress Party, who served as MLC from Chuskhor, and Kacho Mohammad Khan, a retired Naib Tehsildar who entered politics with the support of the revered Ven 19th Kushok Bakula Rinpoche.

Despite the changes over the years, some traditions endure in Kaksar. A few continue to practice the idea of a Sabdak, the family protector, serving as a reminder of the ancient practices of their ancestors. Until recently, Kaksar preserved the practice of Daal or Behan, in which a community member entered a trance to predict future events and provide guidance. However, with the passing of its last practitioner, this unique tradition has come to an end, marking the close of an age-old cultural practice in the region.

|

| Haji Mohammad |

Haji Mohammad, 75, the only son of his parents and a respected landowner from Kaksar, assumed the responsibility of supporting his household at an early age, leaving school to manage the family’s fields. Reflecting on the past, he recalls the immense challenges his ancestors faced in irrigating their fields during the summer months. To address these difficulties, they displayed remarkable ingenuity by constructing a narrow canal system from stones, channeling water from a stream nearly 15 kilometres away in the mountains. This system remains vital for irrigating the village to this day. Although this water source is reliable, the farmers of Kaksar exercise caution in selecting crops, favoring those with low water requirements. Wheat, which Haji Mohammad primarily cultivates, demands less water than barley. In addition, he grows cha and peas in certain fields. Buckwheat (bro), planted in June, is harvested alongside wheat in September, enabling a sustainable agricultural cycle and efficient use of resources.

In his younger years, Haji Mohammad transported wood, known locally as thangshing, to sell in the Kargil market. He typically loaded 12 logs of wood onto a dzho for each trip, earning Rs. 19 per full load. Alongside his wood trade, he also sold sheep in Kargil, fetching prices between Rs. 200 and Rs. 300 per sheep. Usually, Haji Mohammad returned home on the same day after selling the wood. However, on occasions when the wood didn’t sell, he stayed overnight at the Musafirkhana in Kargil. Once his transactions were complete, he and his friends would purchase essentials such as tea, salt, and pul (soda). During those times, tea cost Rs. 13 per kilogram, salt Rs. 1 per kilogram, and pul 25 paise per kilogram in the Kargil bazaar. Most of these trips occurred before the 1960s, as regular vehicular traffic on the main highway began after that, making travel to Kargil more convenient.

|

| Gulam Hussain and Haji Mohammad next to a trunk traditionally used for storing water during the winter months. |

Haji Mohammad vividly recalls the harsh winters of the past, particularly during January and February, when sourcing drinking water posed a significant challenge. To address this, villagers devised an innovative method using winter ice. They hollowed out long wooden trunks to create tubs and placed nets made of wooden branches, known as Changmey Shat, on top. Large chunks of ice were collected and laid on these nets. The tubs were kept in the kitchen, where the heat from the stove melted the ice, allowing water to collect in the hollow trunk for drinking and cooking purposes. With the advent of development, a drinking water pipeline was installed in the village, a transformative milestone that Haji Mohammad credits to the renowned Ladakhi engineer Sonam Norbo. This pipeline, which has been operating continuously since its installation, ensures a reliable and steady supply of water for the villagers.

According to Gulam Hussain, a retired district court employee and a living repository of Kaksar's rich cultural heritage, Sta-Polo was once a highly popular sport in the village. Matches were held at the local polo ground known as the Shagaran. Unfortunately, this historic site is now undergoing construction, marking a significant change in the village's landscape. Another notable cultural tradition centered around a site called Ratho Bao, where horse races were held by men wishing for a son. It was widely believed that the wife of the race winner would give birth to a boy within nine months of the victory, adding a unique element of belief to the event. Kaksar also observed the tradition of animal sacrifice, which played an integral role in the community’s rituals. As part of this practice, a black sheep was sacrificed the day before the harvest to ensure prosperity and abundance. This tradition continued until 1980, when the last recorded sacrifice marked the end of this long-standing custom. Another unique tradition in the village revolves around a day of celebration marked on the 3rd of March. This practice is tied to a local legend in which an ancestor, while returning from Dras, had a brawl with a three eyed demon. The ancestor defeated the demon, who then promised to ensure prosperity for the village, provided he was remembered with a ritual once a year.

|

| Burial-like structures at Zil Do |

|

| Ruins on the hill at Zil Do |

Kaksar is home to three sites of notable archaeological potential. The first two are associated with a mysterious queen, lending an air of intrigue to the local history. The site called Rohni Aeshey (with Rohni meaning queen and Aeshey meaning upper room) is believed to have been her summer fort, while the second site, Koto-Taal, likely served as her winter residence. Both locations, now reduced to ruins, bear little trace of their former grandeur, with much of their structure lost to time. Due to their remote location far from the main village, the author was unable to explore these sites firsthand.

The third site, Zil Do, which was visited, is located to the northeast on the outskirts of the village, and is believed by locals to contain ancient graves alongside the remnants of an old settlement. Portions of the site’s boundary remain visible, providing valuable clues about its original extent. At the foot of the hill lies a long wall resembling a small dam-like structure, which might have been used for water storage in the past. Further along, a cluster of nearly 30 grave-like structures stands out. These burial structures are particularly striking—square in shape and constructed with large surface stones, setting them apart from conventional burial sites. Higher up the hill, remnants of stone structures resembling man-made walls are visible, further evidence of human activity in the area.The hill’s strategic position offers a wide view of the Shingo region, making it an ideal location for an ancient watchtower, similar to those found throughout Ladakh. The unique features and apparent antiquity of Zil Do make it a highly promising candidate for archaeological research, with the potential to uncover significant historical insights into the region’s past.

Phonetic spellings are used for local words to ensure they are transcribed as they were pronounced to the author.